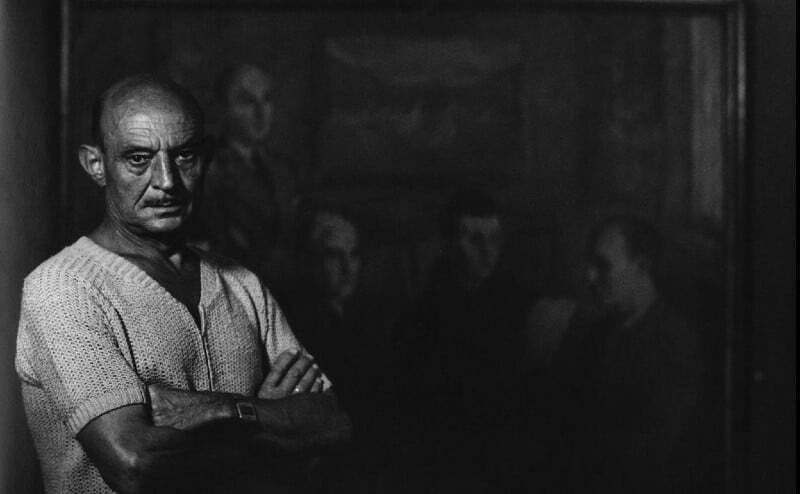

jose iron

The everyday word, loaded with meaning, is the one I prefer. For me the poem must be as smooth and clear as a mirror before which the reader stands.

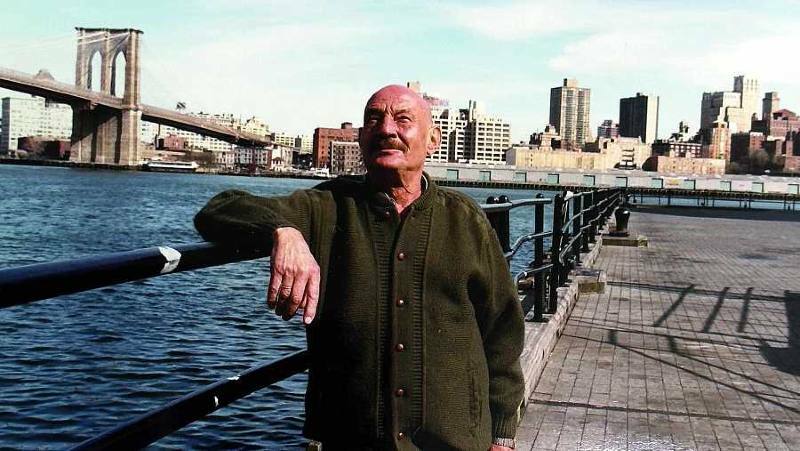

© Photo: Pedro Palazuelos

Nordic has published in November 2022, an impeccable biography of the Madrid poet and Santander fondness, jose iron. Jesus Marchamalo has taken care of the text, being complemented with an anthology of poems, under selection of Lorenzo Olivan.

Born in Madrid in 1922, just two years later the family moved to Santander due to a change of posting of his father, a Telegraph employee. Over there Iron meet the sea, which as well reveals to us bad march, will form part of his entire life and work:

There, Hierro discovered the sea, and the “divine grey” of the bay, so important in his life and work.

The biographer also reveals to us details of his character, from the childhood:

He was, they say about him, a shy, reserved child with few friends, but also cheerful and lively: he liked to go to the beach, swim, and go camping with the scouts. In one of them, in Suances, he won the award for the best paella and always boasted of being an accomplished paellero.

Fan of drawing, music and theater. He began to collaborate with the group Fable. Start reading at Ruben Dario, villaespesa, Juan Ramon Jimenez and one of its most admired writers, Gerardo Diego.

The Baccalaureate is interrupted and he changes to the School of Industries in the specialty of Electromechanical Expertise. Studies that he had to abandon due to the arrival of the war in 1936, when he was 14 years old.

Marchamalo recounts the friendship of Iron with the poet, painter and draughtsman, Jose Luis Hidalgo. Both of them, in 1938, attended an act of Gerardo Diego. They spoke with the poet to deliver him and at the same time that he gave them an opinion on his respective poems. He made an appointment with them, weeks later, but he could only attend Iron, why Nobleman I was mobilized. Pepe brought him as a gift some notebooks of his and Nobleman. Days later the teacher returned them:

Due to a misunderstanding, Gerardo Diego —he thought it was a loan— returned the notebook a few weeks later when Hierro went to visit him to get his opinion. And Hierro, barely a boy yet, did not dare to tell him that it was a gift and he accepted, timid and embarrassed, that he return it to him. The notebook was eventually lost.

The consequences of the Civil War begin to be felt in the family with the imprisonment of joaquin iron, father of the author and affiliated with Izquierda Republicana. He was imprisoned for more than four years and was released in 1941, sick.

The family, in order to survive, had to sell furniture, jewelry and even books. José had to start working cylinder pawn in a factory.

On September 3, 1939, José He is imprisoned accused of subversive activities and transferred on several occasions to different centers of the country. He saw his colleagues shot, which will leave an indelible mark on the poet. He was released on January 1, 1944, arriving in Santander a few days before his father died.

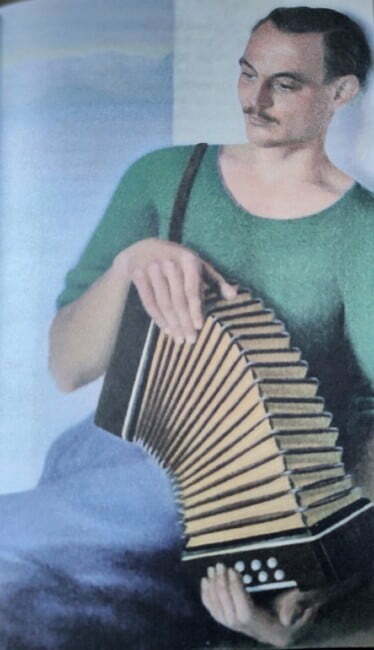

In Santander the climate is rarefied and his friend Jose Luis Hidalgo, from Valencia, convinces him to change scenery. He travels in 1944 with little luggage and a concertina:

In prison he had learned music theory with a cellmate, and music would be decisive in his life and in his poetic production. In fact, he spoke of lyrics and music when he referred to his poetry, and he affirmed that music always came before lyrics.

He settles in the same boarding house as his friend Nobleman. There she met Jorge Campos, Berlanga and the painter Ricardo Zamorano, who would later marry his sister Isabel.

To survive and pay the pension, he worked in everything that came his way:

He was a drainer, home firewood delivery man, commission agent for the sale of books and writer of biographies for an encyclopedia that paid him irregularly at the rate of one peseta per page — three hundred a month typed with two fingers (all his skills were typing)—, and a daily tortilla sandwich.

He returned to Santander in 1946. He worked as a listero in the Monova company and later, in a foundry in Maliaño.

He contacted the Proel group and published his first book in 1947 at the publishing house: earth without us. Among the poems he collects Lorenzo Olivan, It includes arrival at sea, where he appears as the central theme, his beloved Sea, as symbolism Y landscape.

arrival at sea “Tierra sin nosotros” (1947)

Cuando salí de ti, a mí mismo

me prometí que volvería.

Y he vuelto. Quiebro con mis piernas

tu serena cristalería.

Es como ahondar en los principios,

como embriagarse con la vida,

como sentir crecer muy hondo

un árbol de hojas amarillas

y enloquecer con el sabor

de sus frutas más encendidas.

Como sentirse con las manos

en flor, palpando la alegría.

Como escuchar el grave acorde

de la resaca y de la brisa.

Cuando salí de ti, a mí mismo

me prometí que volvería.

Era en otoño, y en otoño

llego, otra vez, a tus orillas.

(De entre tus ondas el otoño

nace más bello cada día).

Y ahora que yo pensaba en ti

constantemente, que creía…

(Las montañas que te rodean

tienen hogueras encendidas).

Y ahora que yo quería hablarte,

saturarme de tu alegría…

(Eres un pájaro de niebla

que picotea mis mejillas).

Y ahora que yo quería darte

toda mi sangre, que quería…

(Qué bello, mar, morir en ti

cuando no pueda con mi vida).

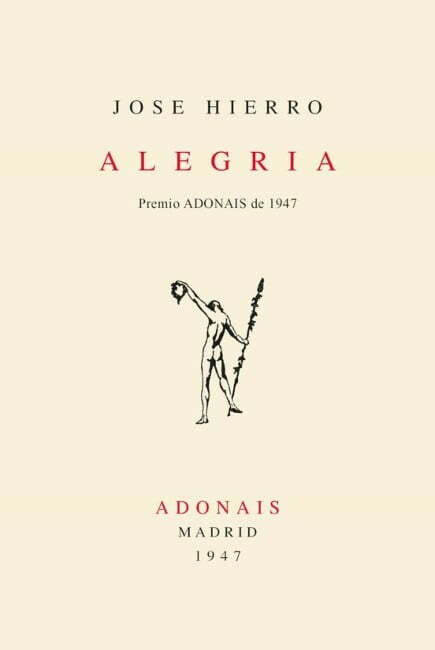

A few months later, the poet delivers his second collection of poems, Joy, with which he would win the prestigious award you adore.

In some interview, jose iron considered the you adore his most beloved award, despite having obtained awards as important as the Prince of Asturias or the cervantes.

Fe de vida “Alegría” (1947)

Sé que el invierno está aquí,

detrás de esa puerta. Sé

que si ahora saliese fuera

lo hallaría todo muerto,

luchando por renacer.

Sé que si busco una rama

no la encontraré.

Sé que si busco una mano

que me salve del olvido

no la encontraré.

Sé que si busco al que fui

no lo encontraré.

Pero estoy aquí. Me muevo,

vivo. Me llamo José

Hierro. Alegría. (Alegría

que está caída a mis pies).

Nada en orden.

Todo roto, a punto de ya no ser.

Pero toco la alegría,

porque aunque todo esté muerto

yo aún estoy vivo y lo sé.

but unfortunately also passes away his great friend, Jose Luis Hidalgo. Iron she often visited him when he was in the hospital. Together with him, she ordered his poems and tried to publish them with the help of friends from Jose Luis, in life; but the edition did not arrive on time, being published posthumously under the title of The dead.

Walk bad march the draftsman facet of the poet:

He drew flowers, seascapes, trees and portraits —frequently also self-portraits— and at lunch or dinner with friends, he absorbed himself painting on the napkins and paper tablecloths that he generously gave away to the guests.

This facet of his as a draftsman would develop in the sixties, in the National Editor. In it he went from office worker to proofreader, then to a layout designer and cover designer; where he designed his book of hallucinations or the one from the book of Francis Threshold, Tamouré.

In 1949 he married Maria Angeles Torres. Discover bad march an anecdote from the day before the wedding of José. He missed the train in Torrelavega and had to borrow a bicycle to catch up with him out of breath at the Barreda stop.

Their first child is born the same year, Juan Ramonin honor of the poet. Pepe He maintained a friendly epistolary relationship with him. In 1951 she was born Daisy; in 1953, Marián and already in Madrid, in 1960, Joaquin.

He works as editor-in-chief at the magazine northern lands and through the Menendez Pelayo International University, will impart courses Y seminars, in addition to practical classes as an assistant, to foreigners. She organizes exhibitions at Casa Proel and publishes her third book with Proel publishing house, With the stones, with the wind, in 1950.

[No quiero que desgranes…] “Con las piedras, con el viento” (1950)

No quiero que desgranes tu pasado en mis manos,

porque sólo el presente ofrece carne viva.

Sería recordar, sentir dolores de otros

doliendo en nuestras vidas.

Serenidad. Se siente el otoño en el alma

caer, con la tristeza de su razón cumplida.

A qué mirar adentro, a la espalda, pensar

en la luz que declina.

Quisiera preguntarte; pero yo me someto.

Contengo la pregunta con la mano en la herida.

No quiero que desgranes tu pasado, que tornes

a lo que no se olvida.

Iron It has built a prestige, but its republican past is not forgotten in Santander and arouses misgivings from institutions related to the Regime. For this reason and a job proposal, he moved to Madrid in 1952. In 1953 he published The fifth of 42 in National Editor. You are also invited to be part of the award jury you adore, getting the prize a young man of 18 years of name, claudio rodriguezwith the work The gift of drunkenness. Paul Beltran publish an anthology of Iron and get in December of the same year, the National Poetry Award.

El Libro “Quinta Del 42” (1952)

Irás naciendo poco

a poco, día a día.

Como todas las cosas

que hablan hondo, será

tu palabra sencilla.

A veces no sabrán

qué dices. No te pidan

luz. Mejor en la sombra

amor se comunica.

Así, incansablemente,

hila que te hila.

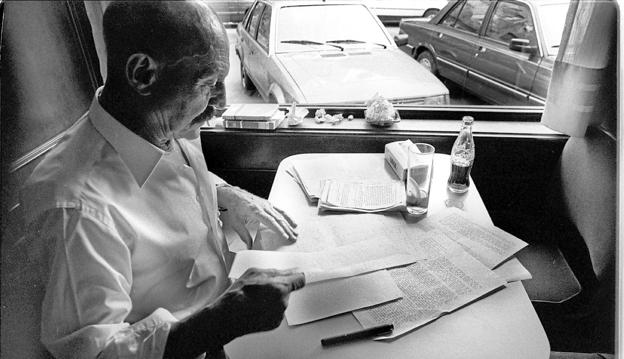

One of the customs jose iron, reveals us bad march what was it write in bars, both from Santander, the Trueba or The rivers, as from Madrid, where he used to frequent The modern.

They would put, without asking, a slightly watery dry chinchón, in a glass, and light a cigarette. She wrote by hand, in notebooks or what was more frequent, on loose sheets in which she crossed out and corrected in a sick way. So much, so repeatedly that he lived with the uncomfortable certainty that he would end up deforesting Europe with his verses.

That was another quality of the writing of jose iron, the slowness due to continuous correction of the texts, where years could pass to deliver definitive versions.

He had several jobs. In the morning, in the National Editor, in the afternoons in the CSIC. Starting in 1968 in the promotion of Reader's Digest, with Luis Rosales Y Fernando Quinones, and in the magazine dunia of chief editor. In the mid-sixties he also began a relationship with National Radio of Spainin cultural programs. He also collaborated in newspapers and magazines. He ran the Poetic Classroom of the Athenaeum. He gave lectures and poetry recitals in Spain and abroad.

In 1955 he published recumbent statues and in 57, How much do I know about myself?, who won the Critics' Award and he John March Award.

Lo efímero “Cuanto sé de mí” (1957)

No me digáis que considere el día

sólo como una ola de lo eterno.

Vendavales vendrán, por el invierno,

que me derrumbarán lo que erigía.

Serenidad me vestirá. Armonía

será mi casa. Exhausto ya tu cuerno,

Fortuna, he de escribir en mi cuaderno:

«Era ilusión tras de lo que corría».

«Razón teníais», os diré. Yo tuve

sinrazones. Fui libre, como nube

que cualquier viento leve la cautiva.

Hablé con vivos y con muertos. Luego,

conmigo y con mi Dios. Decid: «Va ciego».

Pero dejadme, por favor, que viva.

In 1964, with the book of hallucinations he wins again Critics' Award.

Mundo de piedra “Libro de las alucinaciones” (1964)

Se asomó a aquellas aguas

de piedra.

Se vio inmovilizado,

hecho piedra. Se vio

rodeado de aquellos

que fueron carne suya,

que ya eran piedra yerta.

Fue como si las horas,

ya piedra, aún recordaran

un estremecimiento.

La piedra no sonaba.

Nunca más sonaría.

No podía siquiera

recordar los sonidos,

acariciar, guardar,

consolar…

Se asomó al borde mudo

de aquel mundo de piedra.

Movió sus manos y gritó de espanto.

Y aquel sueño de piedra

no palpitó. La voz

no resonó en aquel

relámpago de piedra.

Fue imposible acercarse

a la espuma de piedra,

a los cuerpos de piedra

helada. Fue imposible

darles calor y amor.

Reflejado en la piedra

rozó con sus pestañas

aquellos otros cuerpos.

Con sus pestañas, lo único

vivo entre tanta muerte,

rozó el mundo de piedra.

El prodigio debía

realizarse. La vida

estallaría ahora,

libertaría seres,

aguas, nubes, de piedra.

Esperó, como un árbol

su primavera, como

un corazón su amor.

Allí sigue esperando.

He bought a small country house in Titulcia, near Madrid. She called nayagua, due to the scarcity of water in the area, which he finally achieved with a 25-meter well. He planted different species and ended up being an orchard. He invited writers, painters and colleagues there. He also planted a vineyard and in the eighties he began to bottle wine with the Nayagua label, to give to friends.

He was a heavy smoker. Over time he began to suffer from respiratory problems and despite medical warnings and his wife, Lines; he continued to smoke on the sly, even when he had to carry an oxygen canister in recent years.

it echoes Jesus of the great reciter that he was jose iron, raising waves of enthusiasm among listeners:

Because the emotion of his reading, his sparkling voice, the expressiveness of his hands, with which he seemed to beat the beat to an imaginary orchestra, made the emotion of the poem prevail, even without the audience understanding exactly what it meant. .

It is published in 1991, Diary, a selection of poems distributed in different publications. Twenty-seven years had passed without publishing, except for some anthology.

La casa “Agenda” (1991)

Esta casa no es la que era.

En esta casa había antes

lagartijas, jarras, erizos,

pintores, nubes, madreselvas,

olas plegadas, amapolas,

humo de hogueras…

Esta casa

no es la que era. Fue una caja

de guitarra. Nunca se habló

de fibromas, de porvenires,

de pasados, de lejanías.

Nunca pulsó nadie el bordón

del grave acento: «nos queremos,

te quiero, me quieres, nos quieren…»

No podíamos ser solemnes,

pues qué hubieran pensado entonces

el gato, con su traje verde,

el galápago, el ratón blanco,

el girasol acromegálico…

Esta casa no es la que era.

Ha empezado a andar, paso a paso.

Va abandonándonos sin prisa.

Si hubiera ardido en pompa, todos,

correríamos a salvarnos.

Pero así, nos da tiempo a todo:

a recoger cosas que ahora

advertimos que no existían;

a decirnos adiós, corteses;

a recorrer, indiferentes,

las paredes que tosen, donde

proyectó su sombra la adelfa,

sombra y ceniza de los días.

Esta casa estuvo primero

varada en una playa. Luego,

puso proa a azules más hondos.

Cantaba la tripulación.

Nada podían contra ella

las horas y los vendavales.

Pero ahora se disuelve, como

un terrón de azúcar en agua.

Qué pensará el gato feudal

al saber que no tiene alma;

y los ajos, qué pensarán

el domingo los ajos, qué

pensarán el barril de orujo,

el tomillo, el cantueso, cuando

se miren al espejo y vean

su cara cubierta de arrugas.

Qué pensarán cuando se sepan

olvidados de quienes fueron

la prueba de su juventud,

el signo de su eternidad,

el pararrayos de la muerte.

Esta casa no es la que era.

Compasivamente, en la noche,

sigue acunándonos.

He lives a time in which the awarding of prizes follows one another, highlighting the Prince of Asturias Awards in 1981, The Reina Sofía Prize for Ibero-American Poetry in 1995 and he Cervantes Prize, in 1998.

From 1998 it is also "New York Notebook", his latest book of poems, and with it he achieves the Critics' Award and he national poetry. The book got a unthinkable sales volume for the usual in poetry: more than twenty thousand copies the first year and twelve editions in the following years.

En son de despedida “Cuaderno de Nueva York” (1998)

No vine sólo por decirte

(aunque también) que no volveré nunca,

y que nunca podré olvidarte.

Emprendo la tarea

(imposible, si es que algo hay imposible)

de racionalizar, interpretar, reconstruir y desandar

aquellas fábulas y hechizos

que gracias a ti fueron realidad.

Recupero los pasos iniciados a la orilla del río

y que desembocaban en “Kiss Bar” (aunque no estoy

seguro

dónde estaba el principio y dónde el fin).

Estoy cansado, muy cansado.

Don Antonio Machado dijo hace más de sesenta años

«Soy viejo porque tengo más de setenta años,

que es mucha edad para un español».

(Sin comentarios).

He vivido días radiantes

gracias a ti. Entre mis dedos se escurrían

cristalinas las horas, agua pura. Benditas sean.

Fue un tercer grado carcelario:

regresas a la cárcel por la noche,

por el día ―espejismo― te sientes libre, libre, libre.

Nadie pudo, ni puede, ni podrá por los siglos de los siglos

arrebatarme tanta felicidad.

Yo no he venido ―te lo dije―

para decirte adiós. Sé que no me echarás de menos,

y eso que yo soñaba ser todo para ti

como tú lo eres todo para mí.

¡Ay vanidad de vanidades y todo vanidad!

No te importuno más (ni siquiera sé si me escuchas).

Bebo el último whisky en el «Kiss Bar»,

la última margarita en “Santa Fe”,

rodeo luego la ciudad y su muralla de agua

en la que ya no queda nada que fue mío.

Desisto de adentrarme en su recinto,

no tengo fuerzas para celebrar

la melancólica liturgia de la separación

Sólo deseo ya dormir, dormir,

tal vez soñar…

The book began in 1991, in a stay in New York, at the professor's house Jose Olivio Jimenez, a university professor specializing in postwar Spanish poetry and, as Iron, heavy smoker. The book will be dedicated to him.

He found a bar where to write, the Santa Fe:

In New York, Hierro walked through its streets, letting himself be seduced by the bustle, the light, the architecture, and he looked for a bar to write: the Santa Fe, a semi-basement with a single window facing the street at 73 West 71st Street, where he began to take the first notes of what would end up being one of the greatest books of contemporary Spanish poetry: “I have started some poems about New York,” he declared to a journalist when asked what he was working on. I know it's a cliché, but I don't care”.

I would return to New York repeatedly with long stays.

It is his culminating work. The book presents the love as a dominant theme but under the prism of the old age, of the disease, and with the awareness of pass of the time. It has, in turn, some alcohol references. Iron he was aware of living his last stage, harassed by increasing physical deterioration.

Close the book, the meaning poem, Lifetime, dedicated to his granddaughter Paula:

The book closes with a sonnet, "Vida", one of the most beautiful, unforgettable and exciting in Spanish poetry, which he dedicated to his granddaughter Paula Romero. Although she has ever clarified that it was not really a gift from her, but that she won it in a bet with her grandfather.

tells us bad march what Iron he had promised his granddaughter a poem if she behaved well at a public event in Cantabria. The girl barely moved and at the end of the act she said to her grandfather:

Güelu, I've been great, so “Vida” is mine”. So it was.

Vida “Cuaderno de Nueva York” (1998)

A Paula Romero

Después de todo, todo ha sido nada,

a pesar de que un día lo fue todo.

Después de nada, o después de todo

supe que todo no era más que nada.

Grito “¡Todo!”, y el eco dice “¡Nada!”.

Grito “¡Nada!”, y el eco dice “¡Todo!”.

Ahora sé que la nada lo era todo,

y todo era ceniza de la nada.

No queda nada de lo que fue nada.

(Era ilusión lo que creía todo

y que, en definitiva, era la nada.)

Qué más da que la nada fuera nada

si más nada será, después de todo,

después de tanto todo para nada.

they chose it Academic in 1999. They had proposed it to him several times but he refused because he said he did not feel ready. At the insistence, he finally agreed.

Unfortunately —the biographer tells us— his last years of life were a catalog of illnesses and admissions to hospitals, until his final death:

He died on December 21, 2002 at half past two in the afternoon, in the arms of his granddaughters Paula and Tacha, who were with him in the Carlos III hospital room where he had been admitted days before, suffering from a respiratory crisis.

He was buried in the Pantheon of Illustrious in the Ciriego cemetery, in Santander. The other part of the ashes was thrown into the sea from a sloop. Excited, Jesus concludes:

That sea of his from the north, “north of love” in his own words, sometimes placid, other times roaring and rumors unleashed under the leaden blue, that dagger of light in the bay.

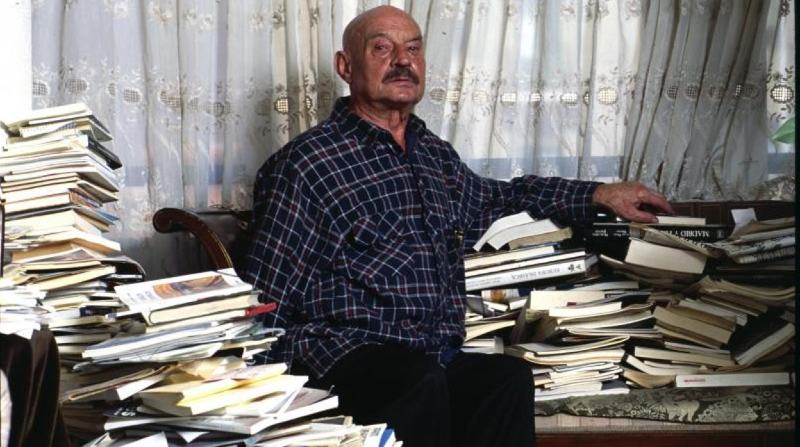

The edition of Nordic It is Excellent. Perfectly laid out, including documents, photographs and drawings of jose iron. The paper quality is superior, with pages in different shades. If to this we add a clear text with the usual good work of Jesus Marchamalo —focusing on the main points of the poet's life—; plus one essential anthology by Lorenzo Olivan, we have one jewel to treasure in the library.

Yes, missing from the anthology, a few brief notes introducing each book of poems. Lorenzo Olivan has been limited to selecting the poems of each book of jose iron, to include them in the work —which are very well selected, that is without a doubt—; but I already say that a few notes on one or two sides in each collection of poems would not have made the work much fatter and would have provided that degree of quality that this careful edition deserved. Small caveats aside, it is a book that should be close on the shelf to enjoy frequently.

bad march deja clara en el libro la vinculación de jose iron con la música. Aunque el poeta afirmaba sentirse frustrado porque le hubiera gustado ser un buen músico, en sus textos poéticos refleja su gusto por la música, no ya observada en el ritmo —musical— que emplea en los poemas, sino también por la propia alusión a sus preferencias musicales: en el poema siguiente de "New York Notebook", his predilection for Schubert and his Quintet in C major.

Adagio para Franz Schubert “Cuaderno de Nueva York” (1998)

(Quinteto en Do mayor)

A Paca Aguirre

I

Apenas vaho sobre el cristal

con ademanes de ceniza, con estelas de niebla,

señala el mayordomo el lugar reservado

a cada uno de los comensales,

y susurra sus nombres con sílabas de ráfaga.

Franz —todos— bebe copas, copas, copas

de un oro ajado, de un resplandor marchito,

una luz madurada en otras tierras

diluidas en la memoria.

¿Dónde estarán los compañeros que no ve?

Acaso fueron arrastrados por las aguas de Heráclito

hasta donde el ocaso se remansa y languidece.

Han cesado las risas. Las palabras son ascuas.

Todo es en este instante

desolación, herrumbre, acabamiento.

Huele a manzanas y a membrillos

demasiado maduros.

A través del ojo de buey

Franz contempla los días

que se aproximan navegando.

La ciudad que lo espera le saluda

con sus brazos alzados a las nubes,

enfundados en terciopelo gris.

Paralizado, congelado, el tiempo

va adquiriendo la pátina de estar atardeciendo

otoñándose sobre el mar,

sobre la muerte, sobre el amor, sobre la música

que se libera, misteriosamente,

de nadie sabe qué prisiones.

II

Esta música lleva mucha muerte dentro.

El amor lleva dentro mucha música,

mucho mar, mucha muerte.

La muerte es un amor que habla con el silencio.

El amor una melodía hija del mar y de la muerte:

asciende, gira, enlaza el cuerpo, lo encadena

hasta asfixiarlo despiadadamente.

III

La nave fantasmal —pero real— navega

sobre al amor, sobre la muerte

(también sobre el olvido),

y glisa sobre el arpa de las olas,

navega sobre el agua como el laúd sobre la música

(y es que música y mar tienen el mismo origen).

Este mar lleva dentro mucha música

mucho amor, mucha muerte.

Y también mucha vida

IV

…Y también mucha vida.

No sólo la que testimonia

el hervor de los brazos blanquísimos de las olas

al otro lado del cristal —solar, lunar— del camarote,

sino la que agoniza en el lado de acá.

Abanicos de plumas y de oro empiezan a girar.

Giran y giran cada vez más vertiginosamente

—acelerando, siempre acelerando—

absorbidos, cautivos, reclamados por bocas abisales,

fraques azules, grises, rumor de besos y batir de alas,

ojos ennoblecidos por las lágrimas,

labios besados hondamente, que por eso

tienen más vida que quitar,

y el giro, el giro, el vértigo del vals,

el del polaco tísico

que escuchaba en la Valldemosa invernal

golpear insistente sobre el suelo la gota de agua.

El vals futuro, felicidad florida

de la dinastía risueña de los vieneses

resucitados cada 1 de enero en los televisores,

supervivientes de un imperio feliz e injusto

que ya no puede ser.

Son absorbidos, chupados, esclavizados

por lo hondo tenebroso. En el embudo

caen y desaparecen gorjeos de las aves

de los bosques de Viena, huéspedes de las ramas

húmedas de los tilos y los abedules,

aroma de grosellas y frambuesas,

de fresas y de arándanos: todos aprisionados

en las redes de escarcha del otoño.

El implacable sumidero

devora tules, sedas, lámparas de luz azulada,

nubes que se suicidan arrojándose

al hueco que termina

en el corazón verde del mar,

en la hoguera sombría y helada de la nada,

en lo fatal, irreversiblemente mudo.

Los invisibles compañeros

contemplan aterrados y desamparados

ese derrumbamiento que acaba en el silencio.

V

…El silencio que surca el ataúd de caoba.

En el silencio Franz contempla, evoca ahora

a sus desvanecidos compañeros.

Con la clarividencia del moribundo

oye su despedida, sus adioses

con voces de violines, de viola, de violonchelos.

Sonaban a diamante y penumbra.

La nave —¿o ataúd?— en que Franz llega,

irremediablemente solo, cabecea sobre las ondas,

las azota su quilla con ritmo sosegado:

—chasquido, pellizcado, pizzicatto sombrío—

entre dos nadas, entre dos nuncas.

VI

…Entre dos nuncas. El recién llegado

contempla el cielo encajonado

entre dos muros, entre dos sombras, entre dos silencios,

entre dos nadas.

Sentado sobre su banco de cemento

saca de su bolsillo unos trozos de pan,

los desmiga. Da de comer a las palomas.

String Quintet D.956 of Franz Schubert, interpretado por The Borodin Quartet With Alexander Buzlov (cello)

José Hierro: words of stone and wind es un reportaje muy recomendable de Radio Nacional de España, con intervenciones del propio poeta,

It is also highly recommended to watch this interview jose iron, made for the united by Edith Czech: